In the binomial probability, we tossed a coin \(n\) times and asked for the probability of getting \(k\) heads. This is the same as picking \(n\) items from a bowl that contains items of \(2\) different colors. For each toss, there are only two possible outcomes: head or tail.

The multinomial probability is a generalization of this. However, instead of having \(2\) colors, our bowl now has items of \(r\) different colors. The probability of picking an item with color \(j\) is \(p_j\) so that

\[p_1+\cdots+p_r=1.\]If we pick \(n\) items from the bowl, what is the probability of getting exactly \(n_i\) items with color \(i\), for each \(i=1,\ldots,r\)? We note that

\[n_1+\cdots+n_r=n.\]Parallel to our discussion on the binomial probability, we find that the probability of getting a specific sequence of colors is

\[p_1^{n_1}p_2^{n_2}\cdots p_r^{n_r}.\]We have to multiply this with the number of sequences with \(n_i\) items of color \(i\). This leads us to the concept of partitions.

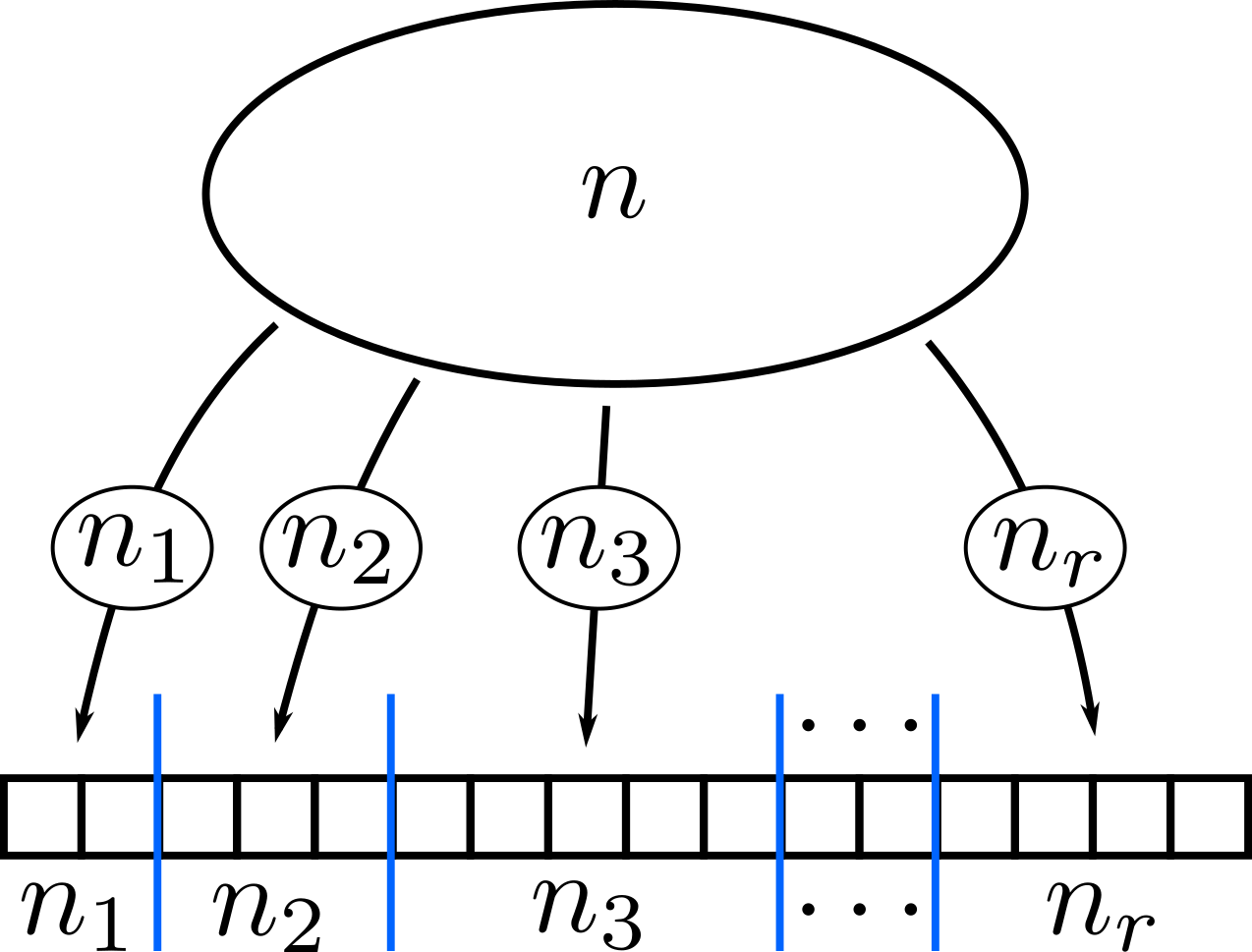

Partitions

Consider a set with \(n\) elements. In how many ways can we partition this set into \(r\) subsets with \(n_1,n_2,\ldots,n_r\) elements? That is, in how many ways can we distribute \(n\) items into \(r\) partitions such that there are \(n_i\) items in partition \(i\)?

The answer is simple. Without restrictions, \(n\) items will have \(n!\) permutations. If we put \(n_i\) items in partition \(i\) and order them, it will still count as one. Consider the word MISSISSIPPI. If we switch any of the I’s, we’d still have the same word! Therefore, the number of ways to partition \(n\) items is

\[\dfrac{n!}{n_1!n_2!\cdots n_r!}.\]This is the multinomial coefficient.

Finally, the probability of picking \(n\) items with \(n_i\) items of color \(i\) (\(i=1,\ldots,r\)) is

\[\dfrac{n!}{n_1!\cdots n_r!}\,p_1^{n_1}\cdots p_r^{n_r}.\]